|

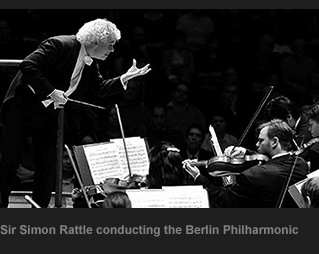

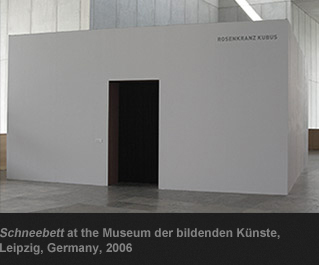

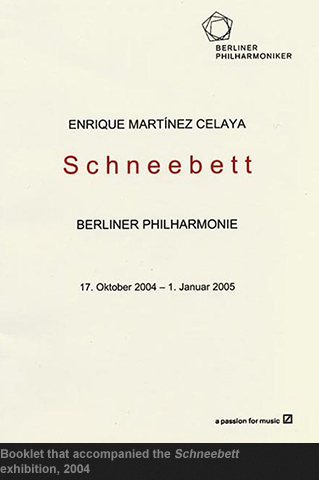

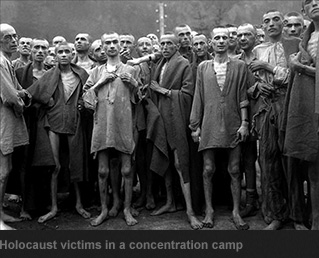

Schneebett (Snow Bed) is a two-room environment that consists of a wax bed cast in bronze and kept frozen through an elaborate refrigeration system; a large painting made of tar and feathers depicting a snow-covered wooded landscape; tree branches that block the connecting passage between the two rooms; a poem, written directly on the wall; and a chair. On view for the first time from 17 October 2004-1 January 2005, it was the first art exhibition ever presented at the Berliner Philharmonie. The title of the piece is taken from a poem by Paul Celan and is the final iteration of Martínez Celaya’s Beethoven Cycle, a three-part reflection on Beethoven’s death. The first exhibition, which was presented in Aspen, addressed the realization of the immanence of death and the second, which was shown in Paris, focused on reconciling a chasm in our lived experience, what Martínez Celaya called “the gap between the self and the part of the self that waits in the past for our return” (Lecture, American Academy in Berlin, 19 October 2004). Schneebett addresses the final moments of Beethoven’s life, as the composer lays in his bed in Vienna, far away from Bonn, his childhood home and without what his biographer Maynard Solomon calls, “the fantasies and delusions of a lifetime” which he labored to strip away during his terminal years (Beethoven 1998, 359). Unable to play music, Beethoven’s art exists only as a memory for the composer and has its final purpose (and ultimate test) as a means to face death. Schneebett embodies the question, what can be learned from the death of another? Schneebett transcended its limits as an artwork or art exhibition, offering an experience that engaged in and was enriched by the nature and culture of Berlin. Martínez Celaya collected dead birch branches from the Tiergarten and incorporated them into the environment, bringing nature inside the Hans Scharoun building, and he also presented a lecture sponsored by the American Academy in Berlin open to the Berlin community. Schneebett’s first viewing was during the Philharmonie’s Tag der Musik when thousands of visitors came to hear music and see the artwork, and afterwards it became part of the Philharmoniker’s concert schedule. To enrich these experiences, the Philharmonie published a booklet with information about the piece that was available for visitors and concertgoers. Although Schneebett emerges from Martínez Celaya’s research on Beethoven’s art and life, especially the last months of his final convalescence in Vienna, Schneebett is not a diorama, a work of historical reconstruction. It is an imaginative meditation, which resembles Andrei Tarkovsky’s film, The Passion of Andrei Rublev (1966), cinematic construction based only loosely on the life of the famous Russian icon painter. Schneebett is framed by nineteenth-century German idealist responses to Kant and animated by the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art.” This nineteenth-century idea of an all-encompassing work that could mobilize and unify the arts attracted and haunted German artists and writers like Novalis, Lessing, Goethe, Wagner, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche. This quest for aesthetic unity also sought to reconnect art to ethics, which had been sundered by Kant. For Martínez Celaya Schneebett is enlisted in the service of life, of human consciousness and its capacity to understand the world, even death. Kurt Schwitters’s epic Hannover Merzbau (1923-1937) and Joseph Beuys’ practice of “social sculpture” of the sixties and seventies are important art historical antecedents that inform Schneebett. Schwitters transforms specific spaces into comprehensive aesthetic environments while Beuys takes artistic practices into the public arena. Although it shares similar interests with Anselm Kiefer’s ambitious installations, such as the poetry of Celan, Heidegger’s writings, and the emotional resonance of Berlin, Schneebett operates on a different emotional register.Unlike Kiefer’s work, which is directed toward excavating and critiquing German national identity, Martínez Celaya’s work in general and Schneebett more specifically, uses the complexities, ambivalences, and tragedies of German culture, including the powerful presence of Jewish thought and feeling, as a means to explore the universal yet diverse experience of exile and loss, memory and longing, and the finality of death. Schneebett marks an important stage in the development of Martínez Celaya’s work. It is the culmination of an intense period of reflection on German writers, artists, and culture, which included a visit to Berlin in 1997 and resulted in photographs and poetry. It also generated thirty-four paintings with emulsified tar and feathers, called the October Cycle (2000-2002), and Coming Home (2001), a project that included drawings, photographs, and a boy and elk made of tar, feathers, and wires. While October Cycle and Coming Home explore the moment of what might be, Schneebett investigates the moment of that which has, or could have, been. From 22 June-30 July 2006, Schneebett was re-created as the inaugural exhibition for the Rosenkranz Kubus at the Museum de bilbeden Kunste in Leipzig, Germany. The installation was installed within viewing distance of Max Klinger’s sculpture of Beethoven. This relation invited the re-consideration of the hero, particularly the nationalist hero, from the point of view of human frailty. Seen in contrast to Klinger’s Beethoven deep in thought amongst angels and with an eagle at his feet, the questions raised by Schneebett are less the heroics of the German Enlightenment than the unresolved conflicts that lead to tragedy and the Holocaust, which has been a consistent concern for Martínez Celaya in earlier projects. Despite its comprehensive and unifying nature, Schneebett opens up gaps and fissures. The bed, cold and hard, is separated from the painting of the snow-covered woods that cannot be entered into and viewed only at the distorted and helpless angle of a bed from which one will never again arise. For Beethoven, for us, the deathbed offers only the occasion for remembering all that the world has had to offer, in art and nature. The birch tree branches also establish a barrier between the viewer and the deathbed. The empty chair is for us, as we can only sit and watch at a distance the death of another and consider our own confrontation with death. The deathbed renders death final, renders it cold and lonely and opens up a chasm, even for those whose religious beliefs presume a God who saves, who resurrects, and gives eternal life. Believer and unbeliever alike must confront the ultimate ethical encounter with the ultimate other, our own finality. Martínez Celaya has written, “the invocation of a great order in the face of nothingness is fundamentally an ethical experience.” (The Prophet, 232). Schneebett, which begins as a monument to Beethoven, becomes our memorial, a mirror through which we confront the memory and value of our own work. The installation of Schneebett at Berlin and Leipzig was partly supported by the noted German collector, Dieter Rosenkranz, who acquired the piece in 2005. Rosenkranz, who has been collecting Martínez Celaya’s work since the mid-nineties, has amassed a comprehensive collection of over forty artworks by the artist. In 2007, while Martínez Celaya’s series of paintings entitled Nomad was on view at the Miami Art Museum, Rosenkranz gifted Schneebett to the museum in support of the its plan for a new building designed by Herzog and de Meuron. Schneebett will be shown for the first time outside of Germany at the Miami Art Museum in the fall of 2011. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||